|

|

|

40 years later, Spider-Man's co-creator is still controversial March 4, 2004 By Franklin Harris Nearly 40 years after leaving Marvel Comics and the characters he helped create there, Steve Ditko remains one of the most talked about and controversial of comic-book artists. He is the subject of a series of essays in the February issue of The Comics Journal (No. 258). And he is the only comic artist discussed as much for his philosophical views as for his artistic contributions.

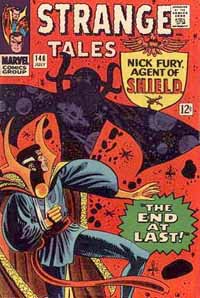

Anyone who knows anything about the early days of Marvel knows Ditko as the co-creator (with Stan Lee) of Spider-Man and Doctor Strange. He also helped to revive the Hulk after that character's first title flopped. During the same period, he drew monster and superhero comics for Marvel's poverty-row competitor, Charlton Comics, where he created The Question, the new Blue Beetle and Captain Atom. And during a brief post-Marvel stint at DC Comics, Ditko created Hawk and Dove, the Creeper and Shade the Changing Man. Ditko's reputation as an artist of comics' Silver Age (1956 to 1970) is second only to Jack Kirby's, and at his best, especially his Doctor Strange stories in "Strange Tales," Ditko is superior to Kirby. Ditko's art has a dynamic quality Kirby's sometimes lacks. His fight scenes are staged as ballets, heroes and villains contorted in ways that are barely possible for normal humans (but appropriate for Spider-Man). In his Comics Journal essay, Bill Randall goes on for three pages just about Ditko's remarkably expressive use of hands. And in the otherworldly settings of his "Strange Tales" stories, even Ditko's backgrounds are in constant motion. Any discussion of Ditko, however, eventually turns to his philosophical and political views. In both cases, his ideas come from Ayn Rand, the 20th century novelist who formulated her own philosophy, which she called Objectivism, and gained a small but rabid following in the early 1960s. More than 20 years after her death, Rand remains a polarizing figure, as much for her abrasive personality as for her views, which embrace reason and free-market capitalism and denounce religion, socialism and anything that restricts individual freedom or creativity. (That Rand's cult-like circle of followers did everything possible to stamp out free thought among its members is another matter.) Obviously, she still provokes hostile reactions, judging from the eagerness of some Journal contributors to slam her. In his otherwise fine piece, Randall begins with a long paragraph on Rand that amounts to rhetorical throat clearing. It's like someone reminding everyone that Nazism is evil before expressing grudging admiration for the cinematic abilities of Leni Riefenstahl. Meanwhile, Craig Fischer blames Rand for the breakup of the Lee/Ditko team. And it is true that Ditko left Marvel after a disagreement with Lee over the Green Goblin's secret identity. In keeping with his philosophy, Ditko thought the villain should turn out to be a nobody. But Lee's view carried the day, and Ditko walked. But it is odd how an artist standing up for his beliefs is a bad thing at the Journal only when the artist is Ditko and the beliefs are Randian. Yes, often Ditko's Objectivism becomes a barrier to storytelling. It motivates the characters in his Question stories for Charlton, but it overwhelms them in his independently published "Static" and "Mr. A" comics. But are critics upset that Ditko is hitting them with a hammer, or are they upset with the particular message he is pounding? Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams' decidedly left-wing "Green Lantern/Green Arrow" comics are equally embarrassing in their earnestness but enjoy an exalted reputation among "socially relevant" comics of the 1970s. What Ditko thinks of all this is anyone's guess. Probably, like one of Rand's characters, he doesn't think about his critics at all. |

RECENT COLUMNS

Order a helping of Cartoon Network's 'Robot Chicken'

03/31/05

Campaign against video games is political grandstanding

03/24/05

Prize-winning author is 'Wrong About Japan'

03/17/05

Censored book not a good start

03/10/05

Some superhero comics are for 'fanboys' only

03/03/05

'Constantine' does well with its out-of-place hero

02/24/05

'80s publisher First Comics' legacy still felt

02/17/05

Director's cut gives new 'Daredevil' DVD an edge

02/10/05

Put the fun back into 'funnybooks'

02/04/05

Is 'Elektra' the end of the road for Marvel movies?

01/27/05

'House of Flying Daggers' combines martial arts and heart

01/20/05

Anniversary edition of 'Flying Guillotine' has the chops

01/13/05

Movie books still have role in the Internet era

01/06/05

Looking ahead to the good and the bad for 2005

12/30/04

The best and worst of 2004

12/23/04

'Has-been' Shatner is a 'transformed man'

12/16/04

© Copyright 2005 PULP CULTURE PRODUCTIONS

Web site designed by Franklin Harris.

Send feedback to franklin@pulpculture.net.